Opening Up Open Science to Epistemic Pluralism

Comment on Bazzoli (2022) and Some Additional Thoughts

The December 2022 issue of the journal Industrial and Organizational Psychology includes a very interesting discussion of the pros and cons of open science. There’s a target article titled “Open science, closed doors: The perils and potential of open science for research in practice” (Guzzo et al., 2022) and nine commentaries on this article. You can find all 10 papers here.

In this post, I focus on Andrea Bazzoli’s (2022) excellent commentary: “Open science and epistemic pluralism: A tale of many perils and some opportunities.” Many thanks to Andrea for drawing my attention to his work on Twitter. I elaborate on some of his points with my own thoughts inspired by Sabina Leonelli’s (2022) recent work.

Open Science Stems from a Postpositivist Research Paradigm

In his article, Bazzoli distinguishes between two research paradigms:

Postpositivism: A research paradigm holding that a knowable, tangible, and measurable reality exists (i.e., naïve or critical realism), knowledge claims about this reality can be developed objectively, and verification/falsification of a priori hypotheses is the most prevalent methodological choice.

Constructionism: A scholarly movement that holds that reality is the result of communicative processes that create a sense of shared reality (i.e., it is locally co-constructed), emphasizes that objectivity is also co-constructed through communicative processes, and aims to examine taken-for-granted realities that might be oppressive or dysfunctional through future-forming, dialogic, hermeneutical, and dialectical research to generate new functional realities.

You can read a bit more about these and other research paradigms in Moin Syed’s (2020) blog post.

It’s important to distinguish between these different research paradigms and their associated research communities because, as Bazzoli explains,

undeclared and unexamined assumptions that are, by definition, self-evident to a community can be seen as impositions by other communities that do not share them (Romaioli & McNamee, 2021). In turn, a given community and its members will defend as reasonable arguments that logically descend from those assumptions against competing communities.

Bazzoli argues that the open science movement is based on the postpositivist research paradigm. Hence, for example, the open science principles of (a) providing a verifiable distinction between hypothesis generation and hypothesis testing, (b) reducing researcher bias, and (c) increasing reproducibility can be seen “as reasonable arguments that logically descend from” a postpositivist epistemology.

Open Science has the Potential to Stifle Scientific Pluralism

Bazzoli argues that:

the open science movement, as a direct offspring of (post)positivist research paradigms, has the potential to stifle epistemological and scientific pluralism and reproduce historical scientific hierarchies it purports to redress.

He’s speaking here of postpositivism as a dominant epistemology in the sciences and arguing that advocating open science also advocates postpositivist epistemology, bolstering its dominance and, potentially, distorting and displacing minority research paradigms that are based on non-postpositivist epistemologies such as constructivism. Hence, at least in its postpositivist form, open science has the potential to stifle scientific pluralism. Bazzoli provides a useful practical example:

There is a movement, especially in Northern Europe, that aims to link adherence to open science practices to tenure and promotion.

For example, in their article “Nudging open science,” Robson et al. (2021) proposed that:

evaluating candidates for hire and promotion in faculties can also be modified to weight open practices more heavily. Such changes are likely to encourage researchers to reconsider their practices and can increase the perception that open practices are not only normative but also valued (Nosek, 2019). Job listings and interview questions could ask for evidence of open practices or for the candidate to illustrate commitment to transparent research in their cover letter. It may also be fruitful to ask candidates to provide an annotated CV detailing whether their articles have been preregistered or openly accessible, what datasets they have openly shared…

These “nudges” may encourage the adoption of open science practices such as preregistration and data sharing. However, they may also encourage the adoption of open science’s postpositivist epistemology. Hence, as Bazzoli points out,

open science serves as a tool to reinforce postpositivism’s hegemonic position in I-O [industrial and organisational] psychology and beyond, to the detriment of other epistemologies.

To be clear, there’s nothing wrong with “nudging” postpositivist researchers to adopt open science research practices. The concern is with nudging non-postpositivist researcher to adopt open science practices. Two potential problems with this approach are assimilation and marginalisation (see also Bazzoli, 2022, p. 527):

Assimilation: Researchers import postpostivist epistemology into their non-postpositivist research paradigms in order to justify their use of newly adopted open science practices. Consequently, their paradigm loses some of its distinctive aspects.

Marginalisation: Non-postpositivist paradigms that don’t adopt open science principles and practices suffer a reduction of resources as a result (e.g., a reduction in jobs, funding, journal space, etc.).

The Case of Qualitative Research

The case of qualitative research has proven to be an important testing ground for the applicability of standard open science practices. What type of data should qualitative researchers share and not share? Is it useful to preregister qualitative studies? Should we expect qualitative results to replicate? The answers to these questions are controversial (for recent discussions, see Branney et al., 2023; Steltenpohl et al., 2021) and, as Bazzoli observes, the controversy runs deeper than simply identifying whether a researcher’s data is represented by numbers or words. It reflects a more fundamental difference in epistemic stances between quantitative and qualitative researchers:

We suggest that it is not qualitative methods, per se, that are at odds with open science principles (as Guzzo et al., 2022, and Pratt, Kaplan, & Whittington, 2020, among others, argued), but the universalistic and all-encompassing claims that are tied to open science are incompatible with epistemic stances most often embraced by qualitative scholars.

In other words, postpositivist open science practices may not fit the non-postpositivist epistemologies employed by qualitative researchers, and indiscriminately encouraging these researchers to adopt such practices may inadvertently compromise their epistemological approach. As Branney et al. (2023) point out,

qualitative researchers, who are increasingly required to engage in open science practices, may feel their research is being judged against quantitative criteria that are inappropriate, irrelevant, or incompatible (Brooks et al., 2018a; Pratt et al., 2020).

But Open Science is Neither Mandatory Nor “One-Size-Fits-All”!

One response to these sorts of concerns is to reassure researchers that the adoption of open science practices is not mandatory. For example, in their commentary on the Guzzo et al. (2022) article, Hüffmeier et al. (2022) explained that:

it is neither the idea underlying OSPs [open science practices] to force researchers to engage in unwanted research practices, nor is there any movement in such a direction.

Another response is to stress that the principles of open science are flexible and adaptive to different disciplinary approaches. For example, in their commentary, Rudolph and Zacher (2022) explained that:

openness is not a monolithic “one size fits all” approach to either science or practice.

Both points are true. Nonetheless, it remains the case that the open science movement is promoting a set of policies and strategies that are designed to reform scientific culture in ways that are consistent with a postpostivist research paradigm. Hence, although researchers are free to choose (a) which open science practices to adopt and (b) how to implement them, they are being encouraged to adopt research practices that are designed for, and carry the assumptions of, a postpositivist research paradigm. Again, this approach is not problematic when researchers are already working within postpositivist research paradigms. The problem only arises when they’re working within non-postpositivist paradigms. In this latter case, we might talk about postpositivist “overreach” or “encroachment” into non-postpositivist research paradigms. (For some examples, please see p. 14 of Beaumont and Coning’s (2022) article: “Coping with complexity: Toward epistemological pluralism in climate–conflict scholarship.”)

Postpositivist Encroachment May Be Motivated and Unacknowledged

The potential for open science’s postpositivist encroachment on non-postpositivist research paradigms may be heightened by two factors. First, scientists may be motivated to universalize their scientific approaches. As Feyerabend (1975) noted:

Scientists are not content with running their own playpens in accordance with what they regard as the rules of scientific method, they want to universalize these rules, they want them to become part of society at large and they use every means at their disposal - argument, propaganda, pressure tactics, intimidation, lobbying - to achieve their aims.

In the case of open science, the motive for widespread propagation of open science practices is an honourable one: to improve the quality, rigour, and credibility of science. The concern is that, although these principles may benefit postpositivist research paradigms, they may be detrimental to non-postpositivist paradigms.

Second, because of its dominance and majority acceptance, the postpositivist research paradigm exerts its influence in a relatively subtle and unacknowledged way. As Kincheloe and Tobin (2015) explained:

many of the tenets of positivism are so embedded within Western culture, academia, and the world of education in particular that they are often invisible to researchers and those who consume their research….The crypto-positivist ideology is not perceived as oppressive and its role in quashing [non-positivist] research is not acknowledged.

Hence, “crypto-positivism” may mislead us into believing that open science principles and practices are universally applicable across all of science when, in fact, those principles and practices are limited to the postpositivist paradigm. This assumption of universality may help to explain universalist slogans such as “open science; just science done right.”

In summary, despite the fact that open science practices are neither mandatory nor one-size-fits-all, there may be an unconscious motive to encourage the uptake of these practices within non-postpositivist research paradigms because they’re believed to be beneficial for science in general. Again, there’s no suggestion of any ill-intentions on the part of the open science movement here. On the contrary, the open science community is clearly attempting to improve the quality, rigour, and credibility of science on the basis of “reasonable arguments that logically descend from…[their postpositivist] assumptions” (Bazzoli, 2022). The concern is that these assumptions do not necessarily apply in the case of non-postpositivist research paradigms.

Pluralist Open Science

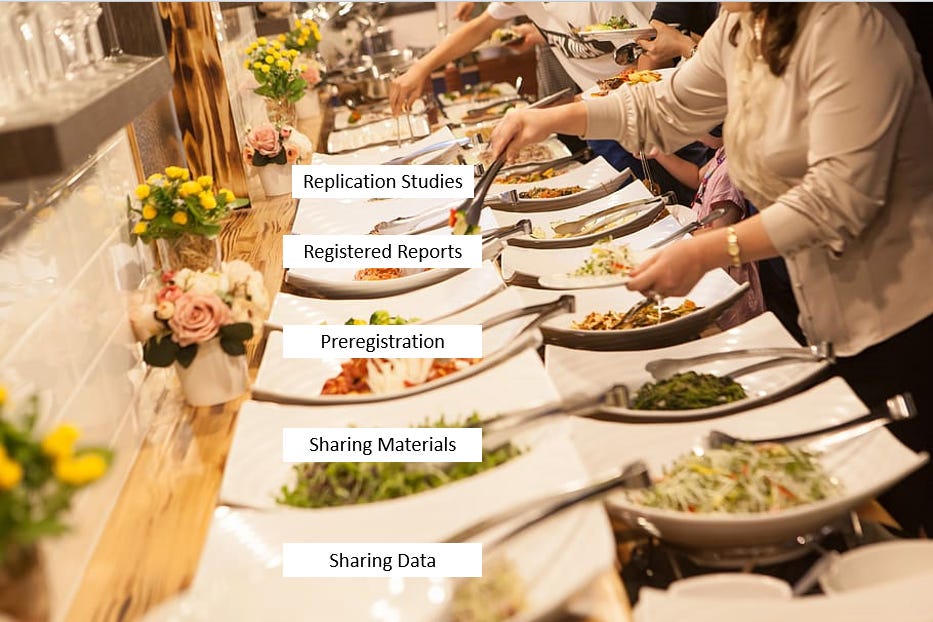

One solution to these potential problems is to open up open science to make it more inclusive and applicable to scientists from non-postpositivist research cultures. In other words, instead of adopting an epistemically monist and assimilatory approach to open science, we could adopt a pluralist and multicultural approach. What might pluralist open science look like? Bergmann’s (2023) recent post on The Buffet Approach to Open Science provides a good starting point:

Open science practices are not all or none, you can pick and choose, match and mix, and do what’s most suitable to your career stage, project, lab, and level of support.

I’d suggest a couple of modifications to the original buffet approach to open science to make it a bit more inclusive. First, we should allow researchers from different research paradigms to create their own open science practices (cook their own dishes!) rather than merely pick and choose from a selection provided by postpositivists. Second, like Bazzoli, I’d argue that researchers from different paradigms should be free to pick and choose (and create) their own open science principles as well as their associated practices. For example, the principle of reproducibility may not apply to non-postpositivist research paradigms. As Bazzoli points out:

constructionist epistemologies are not concerned with replicability of findings at all.

Opening Up Open Science

In her new book, “The Philosophy of Open Science,” Leonelli (2022) explains that the open science movement’s monist view of science is easier to implement but less well suited to address the “rampant plurality” that exists on the ground:

Many of the more institutionalised OS [open science] initiatives tend to privilege a homogenous, universally applicable understanding of the scientific method over a pluralistic and situated one. It is much easier to set up OS guidelines when assuming that science consist of a coherent body of knowledge and procedures that can and should conform to common norms – an assumption that flies in the face of the rampant plurality of research approaches used across domains, locations and contexts.

Certainly, opening up open science within multiple epistemological cultures will be harder than the monist approach because (a) it involves changing multiple scientific cultures, rather than a single scientific culture, and (b) open science principles and practices need to be customised to the needs of particular research paradigms. Opening up open science is also likely to lead to heated discussions between and within different research paradigms about “what ‘open’ and ‘science’ mean” (Bazzoli, 2022, p. 527). As Leonelli (2022) explains:

a key challenge for OS is to productively manage the clash between different interpretations and operationalisations of openness, which emerge from diverse systems of practice with unequal levels of influence and visibility.

One approach to managing this clash is to be more open about not only our methods and data, but also the previously “undeclared and unexamined assumptions” of our research paradigms (Bazzoli, 2022). It’s only after a research paradigm’s epistemic rationales for open science principles and practices are made explicit that its interpretations and operationalisations of openness can be fully understood and appreciated by scientists from other paradigms. Furthermore, it’s only after “judicious connections” (Leonelli, 2022) are made across paradigmatic interpretations and operationalisations that we’ll arrive at a genuinely pluralist open science.

The Article

Bazzoli, A. (2022). Open science and epistemic pluralism: A tale of many perils and some opportunities. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 15(4), 525-528. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2022.67

PDF Download

You can download a PDF version of this article here.

Reference

The reference for this article is as follows:

Rubin, M. (2023, May 4). Opening up open science to epistemic pluralism: Comment on Bazzoli (2022) and some additional thoughts. Critical Metascience. https://doi.org/10.31222/osf.io/dgzxa