A Brief Review of Research that Questions the Impact of Questionable Research Practices

Abstract

Research on questionable research practices (QRPs) includes a growing body of work that questions whether they are as problematic as commonly assumed. This article provides a brief and selective review that considers some of this work. In particular, the review highlights work that questions the prevalence and impact of QRPs, including p-hacking, HARKing, and publication bias. According to this work, QRPs may not provide the best explanation for the replication crisis, and they may not always be problematic. In particular, p-hacking, HARKing, and publication bias may be less impactful than expected.

Questionable Research Practices

Research on questionable research practices (QRPs) includes a growing body of work that questions whether they are as problematic as commonly assumed. One line of work has challenged the view that widespread QRPs are a primary cause of the replication crisis. According to this work, other factors may provide better explanations of the replication crisis, including (a) low statistical power in replication studies, (b) low base rates of true hypotheses, (c) unrealistic expectations about replication rates, and (d) heterogeneous effects (e.g., Bak-Coleman et al., 2024; Bird, 2020; Rubin, 2024; D. J. Stanley & Spence, 2014; T. D. Stanley et al., 2018; Ulrich & Miller, 2020).

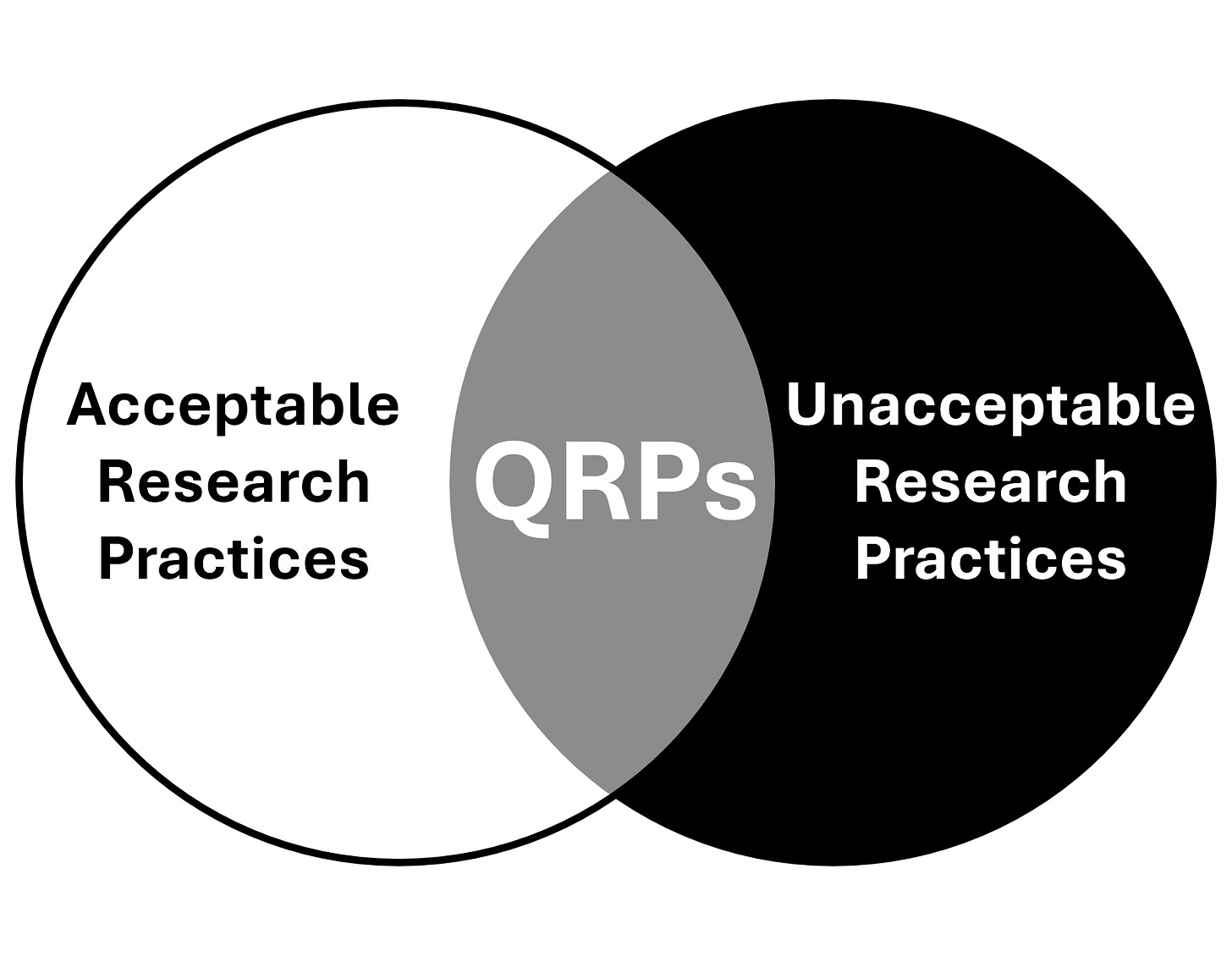

Figure 1. The Presumed Association Between QRPs and the Replication Crisis

A second line of work has argued that we should not assume that QRPs are always problematic. According to this “grey area” interpretation, peers from relevant epistemic communities should consider the implications of particular QRPs for specific research conclusions before determining whether those QRPs are problematic (Kolstoe, 2024, p. 3; Linder & Farahbakhsh, 2020; Rubin, 2023, p. 6; Rubin & Donkin, 2024; Schneider et al., 2024, p. 26). From this perspective, QRPs can sometimes turn out to be acceptable research practices (Fiedler & Schwarz, 2016; John et al., 2012, pp. 3, 531; Larsson et al., 2023, p. 12; Linder & Farahbakhsh, 2020, p. 353; Moran et al., 2022, Table 6; Ravn & Sørensen, 2021; Rubin, 2022, p. 551; Sacco et al., 2019). Furthermore, even unacceptable research practices may not necessarily be regarded as unethical if they are believed to have occurred unintentionally, out of ignorance, or following pressure from powerful others (Erasmus, 2024; Nagy et al., 2025; O’Boyle & Götz, 2022, p. 274; Rubin, 2017, p. 317; Sacco et al., 2019, p. 1323; Schneider et al., 2024, pp. 25-26; Tang, 2024).

Figure 2. The “Grey Area” Interpretation of QRPs

p-Hacking

Although the practice of p-hacking has caused considerable concern, some evidence suggests that it may not be as prevalent as commonly assumed (Adda et al., 2020, p. 29; Fiedler & Schwarz, 2016; Gupta & Bosco, 2023; Hartgerink, 2017; Rooprai et al., 2023; T. D. Stanley et al., 2018). For example, one study of nearly 8,000 psychology articles found that there is “only a small amount of selective reporting bias” (T. D. Stanley et al., 2018, p. 1326). Another study of more than 1,000,000 correlation coefficients found that “the prevalence of p-hacking in organizational psychology is much smaller and less concerning than previous researchers have suggested” (Gupta & Bosco, 2023).

Why might p-hacking be less prevalent than expected? It may be because, in practice, researchers find it difficult to p-hack multiple significant results that are theoretically interesting and directionally consistent when they use conceptually consistent methods and analyses across multiple studies in their research articles (Murayama et al., 2014, pp. 108-109; Wegener et al., 2024).

Finally, when it does occur, the impact of p-hacking on scientific progress may not be as great as anticipated (Fanelli, 2018, p. 2629; Gupta & Bosco, 2023; Head et al., 2015, p. 1). In particular, it has been argued that p-hacking does not inflate statistical Type I error rates in some philosophies of statistics (Rubin, 2024), and that it can have a beneficial effect by increasing researchers’ chances of detecting true positives (Erasmus, 2024; Ulrich & Miller, 2020; see also Ditroilo et al., 2025, p. 5).

Figure 3. Illustration of p-Hacking by XKCD. https://xkcd.com/882/

HARKing

Secretly hypothesizing after the results are known (HARKing) is thought to incur numerous scientific costs (Kerr, 1998). However, the potential harms of HARKing have also been the subject of some debate. For example, concerns about the temporal ordering of (a) the deduction of a hypothesis and (b) researchers’ awareness of an associated test result have been linked to specific types of predictivism that may not be universally endorsed across the scientific community (Dellsén, 2021; Oberauer & Lewandowsky, 2019, p. 1605; Schindler, 2024).

It is also worth considering the potential costs associated with different types of HARKing. In particular, it has been argued that secretly suppressing hypotheses after the results are known (SHARKing) does not bias research conclusions when the suppressed hypotheses are unrelated to those conclusions (i.e., unbiased selective reporting; Leung, 2011; Rubin, 2017; Vancouver, 2018). It has also been argued that secretly retrieving previously-published hypotheses after the results are known and presenting them as a priori hypotheses (RHARKing) “does not pose any threat to science” (Rubin, 2017, p. 315). Finally, it has been argued that secretly constructing hypotheses after the results are known (CHARKing) does not (a) hide circular reasoning, (b) prevent Popperian falsification, (c) cause overfitting, or (d) inflate Type I error rates (Rubin, 2022, 2024; Rubin & Donkin, 2024).

Figure 4. Illustration of HARKing by Dirk-Jan Hoek

Publication Bias

Although publication bias is commonly viewed as a serious threat to science, some work suggests that it may not be as “prominent as feared” (Brodeur et al., 2023, p. 2974); that there is only “weak” evidence of “mild” publication bias in psychology and medicine (Van Aert et al., 2019, p. 1; see also T. D. Stanley et al., 2018); and that it may not have a strong impact on meta-analyses (Dalton et al., 2012; Linden et al., 2024), especially when relevant effects do not feature as “headline results” in studies (Mathur & VanderWeele, 2021, p. 188). It is also worth noting that there are several legitimate reasons for researchers to “file drawer” their work, including some that lead to beneficial forms of publication bias (e.g., a “rigor bias”; Lishner, 2022).

Figure 5. Illustration of File-Drawering by Craig Marker. https://www.craigmarker.com/wp-content/uploads/2006/12/filedrawer1-1002x675.jpg

Summary, Limitations, and Future Work

Based on this brief and selective review, QRPs may not provide the best explanation for the replication crisis, and they may not always be problematic. In particular, p-hacking, HARKing, and publication bias may be less impactful than commonly assumed.

Importantly, this review has only considered research that questions the impact of QRPs. It has not considered research that supports the view that QRPs represent a serious threat to scientific progress. Future reviews in this area should consider both types of research in order to arrive at a more balanced view.

References

Adda, J., Decker, C., & Ottaviani, M. (2020). p-hacking in clinical trials and how incentives shape the distribution of results across phases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(24), 13386-13392. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1919906117

Bak-Coleman, J., Mann, R., Bergstrom, C., Gross, K., & West, J. (2024). Revisiting the replication crisis without false positives. SocArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/rkyf7

Bird, A. (2020). Understanding the replication crisis as a base rate fallacy. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 72(4), 965-993. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjps/axy051

Brodeur, A., Carrell, S., Figlio, D., & Lusher, L. (2023). Unpacking p-hacking and publication bias. American Economic Review, 113(11), 2974-3002. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20210795

Dalton, D. R., Aguinis, H., Dalton, C. M., Bosco, F. A., & Pierce, C. A. (2012). Revisiting the file drawer problem in meta‐analysis: An assessment of published and nonpublished correlation matrices. Personnel Psychology, 65(2), 221-249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2012.01243.x

Dellsén, F. (2021). An epistemic advantage of accommodation over prediction. PhilSci Archive. https://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/19298/

Ditroilo, M., Mesquida, C., Abt, G., & Lakens, D. (2025). Exploratory research in sport and exercise science: Perceptions, challenges, and recommendations. Journal of Sports Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2025.2486871

Erasmus, A. (2024). p-hacking: Its costs and when it is warranted. Erkenntnis, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-024-00834-3

Fanelli, D. (2018). Is science really facing a reproducibility crisis, and do we need it to? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(11), 2628-2631. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1708272114

Fiedler, K., & Schwarz, N. (2016). Questionable research practices revisited. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(1), 45-52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615612150

Friese, M., Loschelder, D. D., Gieseler, K., Frankenbach, J., & Inzlicht, M. (2019). Is ego depletion real? An analysis of arguments. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 23(2), 107-131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868318762183

Gupta, A., & Bosco, F. (2023). Tempest in a teacup: An analysis of p-hacking in organizational research. PLOS One, 18(2), e0281938. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281938

Hartgerink, C. H. J. (2017). Reanalyzing Head et al. (2015): Investigating the robustness of widespread p-hacking. PeerJ, 5:e3068. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3068

Head, M. L., Holman, L., Lanfear, R., Kahn, A. T., & Jennions, M. D. (2015). The extent and consequences of p-hacking in science. PLOS Biology, 13.3: e1002106. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002106

John, L. K., Loewenstein, G., & Prelec, D. (2012). Measuring the prevalence of questionable research practices with incentives for truth telling. Psychological Science, 23(5), 524–532. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611430953

Kerr, N. L. (1998). HARKing: Hypothesizing after the results are known. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2(3), 196-217. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0203_4

Kolstoe, S. (2024). Questionable research practices (UKRIO). https://doi.org/10.37672/UKRIO.2023.02.QRPs

Larsson, T., Plonsky, L., Sterling, S., Kytö, M., Yaw, K., & Wood, M. (2023). On the frequency, prevalence, and perceived severity of questionable research practices. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics, 2(3), 100064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmal.2023.100064

Leung, K. (2011). Presenting post hoc hypotheses as a priori: Ethical and theoretical issues. Management and Organization Review, 7(3), 471–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2011.00222.x

Linden, A. H., Pollet, T. V., & Hönekopp, J. (2024). Publication bias in psychology: A closer look at the correlation between sample size and effect size. PLOS One, 19(2), e0297075. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297075

Linder, C., & Farahbakhsh, S. (2020). Unfolding the black box of questionable research practices: Where is the line between acceptable and unacceptable practices? Business Ethics Quarterly, 30(3), 335–360. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2019.52

Lishner, D. A. (2022). Sorting the file drawer: A typology for describing unpublished studies. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(1), 252-269. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620979831

Mathur, M. B., & VanderWeele, T. J. (2021). Estimating publication bias in meta‐analyses of peer‐reviewed studies: A meta‐meta‐analysis across disciplines and journal tiers. Research Synthesis Methods, 12(2), 176-191. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1464

Moran, C., Richard, A., Wilson, K., Twomey, R., & Coroiu, A. (2022). I know it’s bad, but I have been pressured into it: Questionable research practices among psychology students in Canada. Canadian Psychology, 64(1), 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000326

Murayama, K., Pekrun, R., & Fiedler, K. (2014). Research practices that can prevent an inflation of false-positive rates. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(2), 107-118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868313496330

Nagy, T., Hergert, J., Elsherif, M., Wallrich, L., Schmidt, K., Waltzer, T., Payne, J. W., Gjoneska, B., Seetahul, Y., Wang, Y. A., Scharfenberg, D., Tyson, G., Yang, Y.-F., Skvortsova, A., Alarie, S., Graves, K., Sotola, L. K., Moreau, D., & Rubínová, E. (2025). Bestiary of questionable research practices in psychology. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/fhk98_v2

Oberauer, K., & Lewandowsky, S. (2019). Addressing the theory crisis in psychology. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 26, 1596–1618. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-019-01645-2

O’Boyle, E. H., & Götz, M. (2022). Questionable research practices. In L. J. Jussim, J. A. Krosnick, & S. T. Stevens (Eds.), Research integrity: Best practices for the social and behavioral sciences (pp. 260-294). Oxford University Press.

Ravn, T., & Sørensen, M. P. (2021). Exploring the gray area: Similarities and differences in questionable research practices (QRPs) across main areas of research. Science and Engineering Ethics, 27(4), 40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-021-00310-z

Rooprai, P., Islam, N., Salameh, J. P., Ebrahimzadeh, S., Kazi, A., Frank, R., Ramsay, T., Mathur, M. B., Absi, M., Khalil, A., Kazi, S., Dawit, H., Lam, E., Fabiano, N., & McInnes, M. D. (2023). Is there evidence of p-hacking in imaging research? Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal, 74(3), 497-507. https://doi.org/10.1177/08465371221139418

Rubin, M. (2017). When does HARKing hurt? Identifying when different types of undisclosed post hoc hypothesizing harm scientific progress. Review of General Psychology, 21(4), 308-320. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000128

Rubin, M. (2022). The costs of HARKing. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 73(2), 535-560. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjps/axz050

Rubin, M. (2023). Questionable metascience practices. Journal of Trial and Error, 4(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.36850/mr4

Rubin, M. (2024). Type I error rates are not usually inflated. Journal of Trial and Error, 4(2), 46-71. https://doi.org/10.36850/4d35-44bd

Rubin, M., & Donkin, C. (2024). Exploratory hypothesis tests can be more compelling than confirmatory hypothesis tests. Philosophical Psychology, 37(8), 2019-2047. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2022.2113771

Sacco, D. F., Brown, M., & Bruton, S. V. (2019). Grounds for ambiguity: Justifiable bases for engaging in questionable research practices. Science and Engineering Ethics, 25(5), 1321-1337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-018-0065-x

Schindler, S. (2024). Predictivism and avoidance of ad hoc-ness: An empirical study. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 104, 68-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsa.2023.11.008

Schneider, J. W., Allum, N., Andersen, J. P., Petersen, M. B., Madsen, E. B., Mejlgaard, N., & Zachariae, R. (2024). Is something rotten in the state of Denmark? Cross-national evidence for widespread involvement but not systematic use of questionable research practices across all fields of research. PLOS One, 19(8), e0304342. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0304342

Stanley, D. J., & Spence, J. R. (2014). Expectations for replications: Are yours realistic? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(3), 305-318. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614528518

Stanley, T. D., Carter, E. C., & Doucouliagos, H. (2018). What meta-analyses reveal about the replicability of psychological research. Psychological Bulletin, 144(12), 1325-1346. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000169

Tang, B. L. (2024). Deficient epistemic virtues and prevalence of epistemic vices as precursors to transgressions in research misconduct. Research Ethics, 20(2), 272-287. https://doi.org/10.1177/17470161231221258

Ulrich, R., & Miller, J. (2020). Questionable research practices may have little effect on replicability. Elife, 9, e58237. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.58237

Van Aert, R. C., Wicherts, J. M., & Van Assen, M. A. (2019). Publication bias examined in meta-analyses from psychology and medicine: A meta-meta-analysis. PLOS One, 14(4), e0215052. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215052

Vancouver, J. N. (2018). In defense of HARKing. Industrial and Organizational Psychology. 11(1), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2017.89

Wegener, D. T., Pek, J., & Fabrigar, L. R. (2024). Accumulating evidence across studies: Consistent methods protect against false findings produced by p-hacking. PLOS One, 19(8), e0307999. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0307999

Citation

Rubin, M. (2025). A brief review of research that questions the impact of questionable research practices. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ah9wb_v3