What is Critical Metascience and Why is it Important?

This post is based on a presentation I gave in June 2025 as part of a Metascience 2025 Preconference Virtual Symposium convened by Sven Ulpts and Sheena Bartscherer and including Thomas Hostler, Lai Ma, Lisa Malich, and Carlos Santana. The symposium was called Critical metascience: Does metascience need to change?, and you can find a recording here.

What is Metascience?

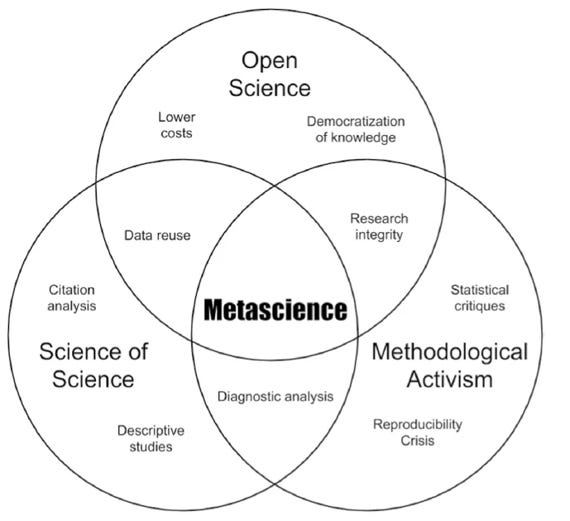

Modern metascience took off in the 2010s in response to the replication crisis and concerns about research integrity, and it’s been “exploding” in the last year (Tim Errington, quoted in “Metascience can improve science,” 2025). But what exactly is metascience? There are several definitions (UK Metascience Unit, 2025, pp. 4-5), but I like Peterson and Panofsky’s (2023) approach of locating metascience at the intersection of the science of science, open science, and methodological activism.

Expanding on Peterson and Panofsky’s (2023) approach, we can distinguish between three types of metascience. Basic metascience use a scientific approach to understand and critique the way we do science. Applied metascience designs and tests interventions to improve science. Finally, activist metascience is a more organized approach focused on reforming research culture by changing norms, incentives, and policies in line with open science principles (e.g., Grant et al., 2025; Nosek, 2019; Nosek et al., 2012). Importantly, it’s this latter “activist reform movement” (Vazire & Nosek, 2023, p. 3) that dominates modern metascience, setting the agenda for both basic and applied metascience (Bastian, 2021; Nielsen & Qiu, 2018; Peterson & Panofsky, 2021, 2023).

What is Critical Metascience?

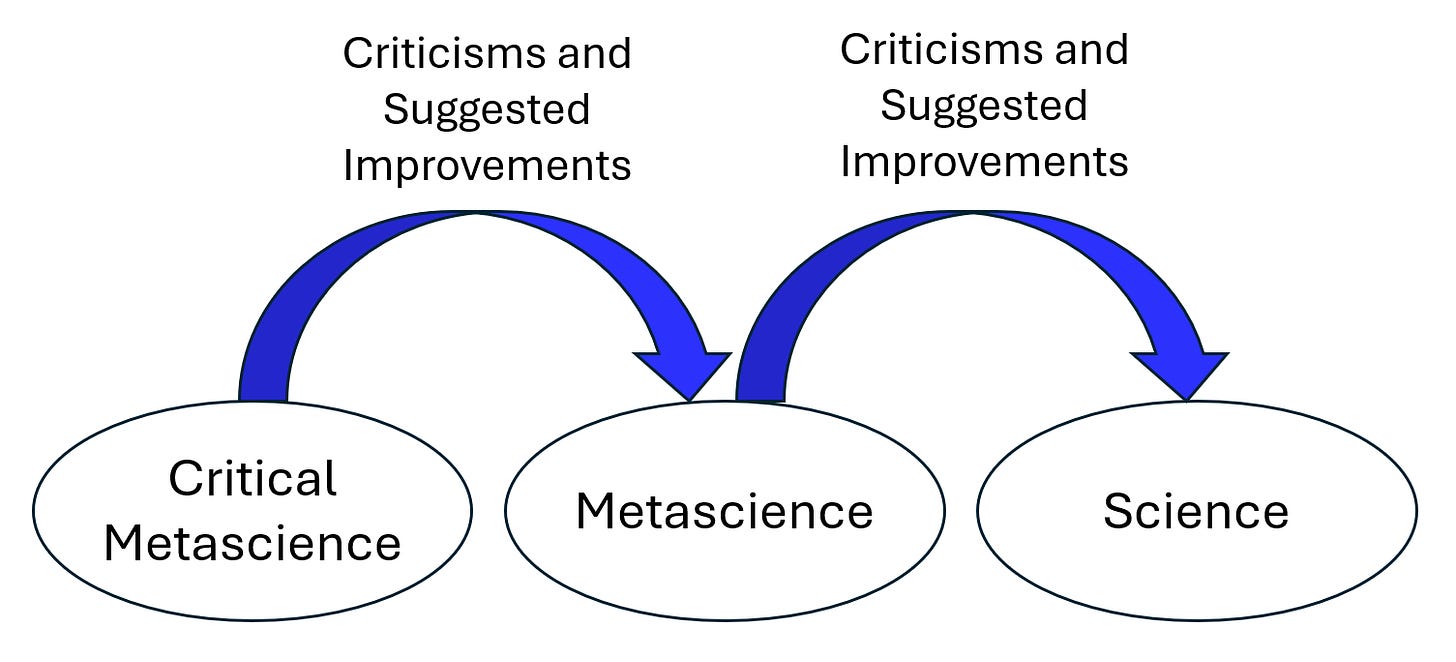

So, what’s critical metascience? Well, I’d define critical metascience as a multi-disciplinary approach that takes a step back to question some of metascience’s commonly-accepted assumptions, methods, problems, and solutions. For this reason, critical metascience has also been described as “meta-meta-science” (Quintana & Heathers, 2023), and I think that term works well because it captures the idea that, if science is the subject of metascience, then metascience is the subject of critical metascience! However, the “critical” part of critical metascience means that we’re not just passively studying metascience; we’re also actively criticizing some of its key assumptions and making suggestions for improvements.

So, in my view, “critical metascience” doesn't mean “metascientists who are critical” because metascientists are critical of themselves and others all the time. Instead, “critical metascience” refers to a special type of criticism that challenges metascience’s dominant ideas and assumptions and offers new, countervailing perspectives. Hence, the word “critical” refers to disruptive, paradigmatic criticism (e.g., “Questionable research practices [QRPs] are not necessarily problematic”) rather than more specific, conventional criticism that implicitly accepts the paradigm’s assumptions (e.g., “This measure of QRPs is not reliable”).

It’s also worth noting that “critical metascience” doesn’t necessarily imply a negative or contrarian stance. It can also provide constructive criticism. For example, although critical metascience may critique some science reforms, such as preregistration (e.g., Pham & Oh, 2021a, 2021b), it may also recommend alternative reforms, such as researcher reflexivity (e.g., Field & Pownall, 2025; Steltenpohl et al., 2023), as well as alternative implementations of current reforms (e.g., Bazzoli, 2022; Kessler et al., 2021).

Why is Critical Metascience Important?

Why is critical metascience important? Well, in a nutshell, I think it can help to highlight and address collective biases in metascience. Of course, all scientific fields have biases. However, metascience’s biases may be particularly problematic because they’re heavily influenced by its activist open science reform movement. As Hauswald (2021) explained:

If…the community of an entire research field is dominated by scholars with a particular activist affiliation…[and] if many or all members are biased in the same direction, their biases accumulate, as it were, to a collective bias. From a pluralist point of view, a dominance of persons with a particular activist background appears to be epistemically detrimental insofar as it reduces epistemic diversity. Research fields that are intimately connected to particular activist movements therefore seem to be particularly prone to such collective biases.

Hence, it’s possible that the dominance of the activist reform movement may reduce epistemic diversity within metascience. This is not to dispute the good intentions of open science reformers. It’s only to point out that the collective dominance of the assumptions behind those intentions may have a detrimental effect on the field’s epistemic approach (Bashiri et al., 2025, p. 9; Bazzoli, 2022; Rubin, 2023a; Rubin, 2023b, pp. 7-9).

Hauswald (2021) also predicts “the presence of various social mechanisms that produce or reinforce collective biases in such fields” (p. 612). And, sure enough, these sorts of “social mechanisms” have been observed in metascience (e.g., Bastian, 2021; Flis, 2022; Gervais, 2021; Hamlin, 2017, p. 692; Malich & Rehmann-Sutter, 2022, p. 265; Rubin, 2023b; Whitaker & Guest, 2020; Walkup, 2021). For example, Bastian (2021) noted that:

“Us and them” thinking and movement camaraderie lead some people to see criticism of fellow-travelers as “friendly fire” that’s out of line, leading them to keep criticisms to themselves. Advocates can also be very quick to jump into defensive attack mode instead of reflection when anyone criticizes. The combination of deterring incisive analysis and not engaging deeply with confronting thoughts is a shortcut to blinding yourself to movement and theory errors.

And this is where I think critical metascience can be helpful, because it deliberately steps back to reconsider some of metascience’s common assumptions, including implicit background assumptions that may be invisible from within the movement’s research culture (Kim et al., 2000, p. 68; Longino, 1990, p. 80; Popper, 1994, p. 135).

To be clear, I’m not arguing that critical metascientists are less biased than metascientists. I am only arguing that they tend to have different and more diverse biases, and that it may be useful to take their perspectives into account in order to increase epistemic diversity (Hauswald, 2021; Hull, 1988; Longino, 1990; O’Rourke-Friel, 2025; Rubin, 2023a). Similarly, I’m not arguing that activist metascience can’t improve science or that critical metascientists can’t also be activists. I am only arguing that activist metascience is susceptible to collective biases about what “science” is and how best to “improve” it, and that critical metascience can help to highlight and address these biases.

Questioning Some Common Metascience Assumptions

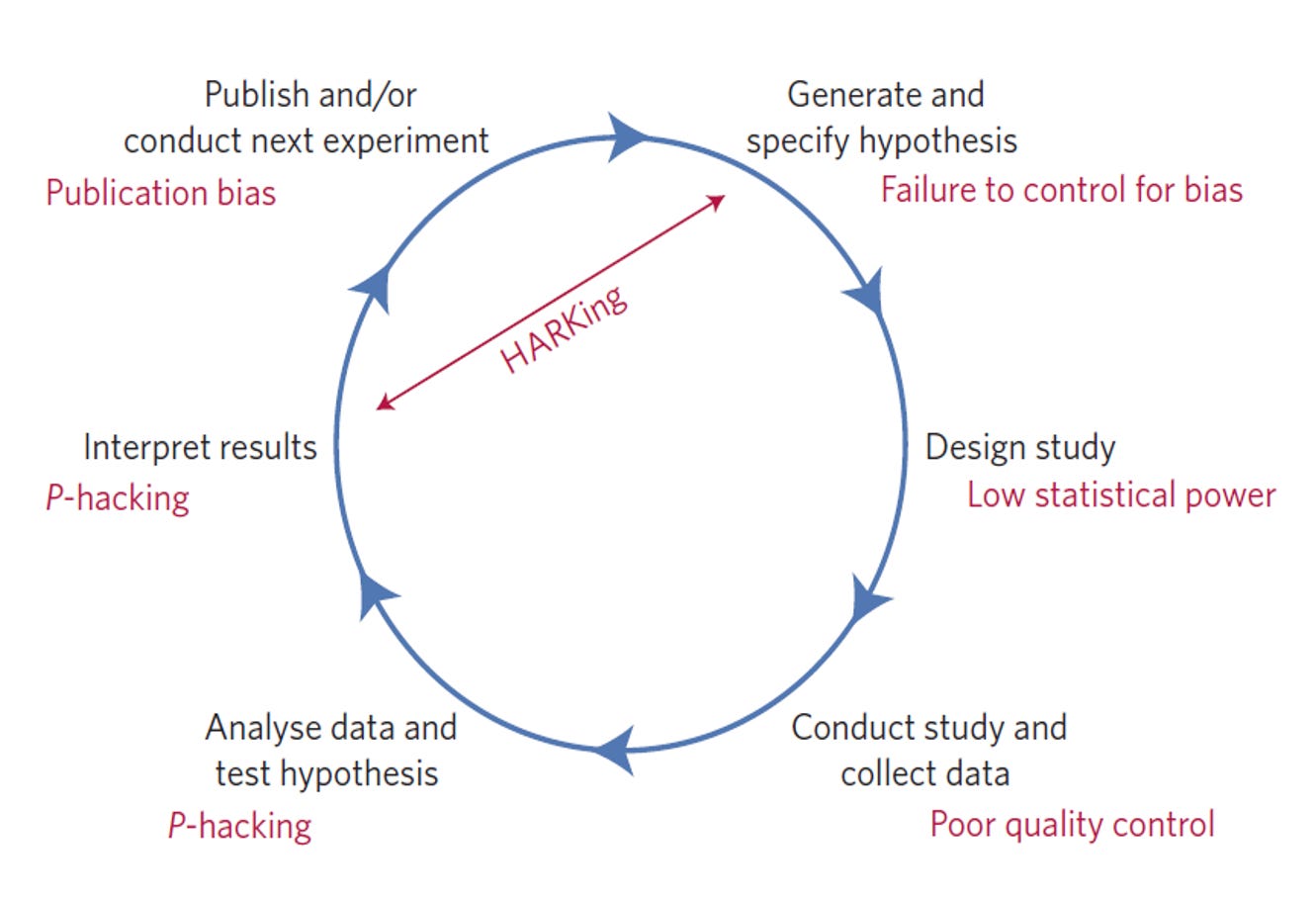

What are some of metascience’s core assumptions? Well, this famous figure from Munafò et al.’s (2017) “Manifesto for Reproducible Science” provides a few examples (see also Chambers et al., 2014).

According to Munafò et al. (2017), researcher bias, low statistical power, HARKing, p-hacking, and publication bias lead to false positives and, consequently, low replication rates. Now, there’s certainly good evidence and reasonable arguments to warrant each of these concerns. For example, metascientists and others often agree that:

Exploratory results are more “tentative.” E.g., Hardwicke & Wagenmakers (2023); Nelson et al. (2018); Nosek & Lakens (2014); Simmons et al. (2021b); Wagenmakers et al. (2012)

QRPs are problematic. E.g., Agnoli et al. (2017); Banks et al. (2016); Fraser et al. (2018); Hartgerink & Wicherts (2016); Miller et al. (2025); Pickett & Roche (2018)

E.g., 1: HARKing is problematic. E.g., Bishop (2019); Bosco et al. (2016); Kerr (1998); O’Boyle et al. (2014).

E.g., 2: p-hacking is problematic. E.g., Bishop (2019); Nagy et al. (2025); O’Boyle & Götz (2022); Reis & Friese (2022); Simmons et al. (2011); Stefan & Schönbrodt (2023); Wicherts et al. (2016)

Publication bias is problematic. E.g., Bishop (2019); Chambers & Tzavella (2022); Errington et al. (2021); Schimmack (2020)

Low replication rates are problematic. E.g., Baker (2016); Open Science Collaboration (2015); Munafò et al. (2017); Pashler & Wagenmakers (2012); Schimmack (2020); Wingen et al. (2020)

These six claims are now so widely accepted within metascience that they’re treated as almost indisputable facts! In this sense, they form part of an irrefutable Lakatosian “hard core” in the movement’s research program (Lakatos, 1978). Critically, however, Lakatosian research programs grow by qualifying their hard cores with auxiliary hypotheses that accommodate anomalies and make successful new predictions (e.g., “low replication rates are problematic in Situation X but not in Situation Y”; Lakatos, 1978, pp. 21, 50, 179). The problem is that this theoretical progress appears to be lacking in metascience, suggesting that the field may be in a pseudoscientific state (Lakatos, 1978, pp. 33-34).

Metascience’s limited theoretical progress can’t be attributed to the absence of important empirical and theoretical discrepancies. For example, there’s now good evidence and arguments that challenge the generality of each of the previous six claims and call for some nuance in their articulation (for a brief review, see Rubin, 2025a):

Exploratory results are more “tentative.” BUT SEE: Devezer et al. (2021); Feest & Devezer (2025); Rubin (2017a); Rubin & Donkin (2024); Szollosi & Donkin (2021)

QRPs are problematic. BUT SEE: Fiedler & Schwarz (2016); Linder & Farahbakhsh (2020); Moran et al. (2022, Table 6); Ravn & Sørensen (2021); Rubin (2023b); Sacco et al. (2019); Ulrich & Miller (2020)

E.g., 1: HARKing is problematic. BUT SEE: Leung (2011); Oberauer & Lewandowsky (2019); Mohseni (2020); Rubin (2017b, 2022); Vancouver (2018)

E.g., 2: p-hacking is problematic. BUT SEE: Adda et al. (2020); Erasmus (2024); Gupta & Bosco (2023); Hartgerink (2017); Rooprai et al. (2023); Rubin (2024); Stanley et al. (2018); Ulrich & Miller (2020); Wegener et al. (2024)

Publication bias is problematic. BUT SEE: Brodeur et al. (2023); Dalton et al. (2012); Linden et al. (2024); Mathur & VanderWeele (2021); Ramos (2025); Van Aert et al. (2019)

Low replication rates are problematic. BUT SEE: De Boeck & Jeon (2018); Devezer et al. (2019, 2021); Fanelli (2018); Feest (2019); Firestein (2012, 2016); Greenfield (2017); Guttinger (2020); Haig (2022); Iso-Ahola (2020); Leonelli (2018); Lewandowsky & Oberauer (2020); Pethick et al. (2025); Rubin (2023b, 2025b); Stroebe & Strack (2014)

Isn’t this work just standard self-critical metascience in action? Perhaps it should be, and maybe some of it is! However, if this sort of work was genuinely accepted as standard metascience, then it would be met with less defensiveness (Bastian, 2021; Flis, 2022; Gervais, 2021; Hamlin, 2017; Malich & Rehmann-Sutter, 2022, p. 265; Walkup, 2021), and its conclusions would be better integrated into the field to produce more complex and nuanced models of science (Greenwald et al., 1986, pp. 223-224; Lakatos, 1978, p. 50; Russell, 1912, p. 8). Instead, with few exceptions, “critical” work like this tends to be less acknowledged than standard metascience (Flis, 2022; Horbach et al., 2024; Rubin, 2023b), and relatively simplistic models endure (Flis, 2019, p. 170; Peterson & Panofsky, 2023, p. 169; Pham & Oh, 2021b, p. 168). This is a shame because it’s precisely this type of work that we should be paying attention to if we want to tailor the right kinds of reforms to the right areas and implement them in the right ways.

Hence, in practice, “critical” work that questions common metascience assumptions is not usually treated as standard metascience. Indeed, its calls for caution, caveats, and nuance may be viewed as challenging metascience’s more universalist claims of science-wide “crises” (Jamieson, 2018; Penders, 2024, p. 3).

Why does Metascience need Critical Metascience?

Why does metascience need a special, separate, “critical” field? What makes it different from other disciplines in this respect? Well, in fact, some other disciplines also have critical fields. For example, psychology has critical psychology (Parker, 2007), and, more recently, the area of critical data studies has arisen to question dominant views in data science (Iliadis & Russo, 2016).1 But there are some unique aspects of metascience that make critical metascience particularly useful.

First, modern metascience arose in response to a “crisis” about replication and research integrity (Nielsen & Qiu, 2018; Pashler & Harris, 2012; Schooler, 2014). The problem is that, in a crisis, people often respond with a biased cognitive style. For example, they might experience a range of negative moral emotions, have a narrow focus on specific issues, submit to autocratic decision-making, and engage in consensus-seeking and groupthink (e.g., Antonetti et al., 2025; Paulus et al., 2022; Turner & Pratkanis, 1998). So, it’s helpful to get the views of people who are not operating in this crisis mode.

Second, metascience is heavily influenced by psychologists because psychology was ground zero for the replication crisis (Open Science Collaboration, 2015). But this influence may give the field a somewhat unrepresentative view of science and its problems (Flis, 2019; Malich & Rehmann-Sutter, 2022; Moody et al., 2022; Morawski, 2022). Consequently, as Gervais (2021) argued, “a movement that has emerged from critical reflection on psychological science should be open to critical self-reflection on its own workings and open to wisdom and critiques from other fields that may have important theoretical insights” (p. 828; see also Hamlin, 2017, p. 691). Critical metascience’s multi-disciplinary, paradigmatic criticism can help to provide these insights.

Third, activist metascience can be construed as a moral crusade to save science from self-interested scientists operating in a dysfunctional incentive system (Bastian, 2021; Knibbe et al., 2025; Morawski, 2020; Nosek et al., 2012; Penders, 2024; Peterson & Panofsky, 2023; Robinson-Greene, 2017). According to this view, activist metascientists may sometimes experience a “white hat bias” (Lilienfeld, 2020, p. 2) and feel morally justified in summarily ignoring or dismissing criticisms of science reforms. Consequently, as Bastian (2021) explained, “we need a broad approach to risk of bias in metascience, that encompasses our high risk of confirmation bias and ideological thinking.”

Finally, and more generally, it’s important to appreciate that critical metascience has the same rationale as metascience; it’s just pitched at a higher level of abstraction (i.e., it’s “meta-meta-science”). Hence, it would be inconsistent to argue that we need a special field to criticize and improve the way we do science (i.e., metascience), but that we don’t need a special field to criticize and improve the way we do metascience (i.e., critical metascience)!2

Some Emerging Themes in Critical Metascience

Unlike metascience, critical metascience doesn’t have a coherent narrative (e.g., QRPs > false positives > replication crisis). Nonetheless, we can identify some emerging themes in the area.

One line of work has questioned the meaning and interpretation of replication failures, arguing that low replication rates may not (a) represent a “crisis” and (b) occur throughout science (e.g., Fanelli, 2018; Firestein, 2016; Haig, 2022; Lewandowsky & Oberauer, 2020; Pethick et al., 2025; Stroebe & Strack, 2014).

Another line of work has argued that metascience is too heavily focused on replication, statistics, and methods, and that this preoccupation may encourage naïve empiricism, statisticism, and methodologism respectively (e.g., Haig, 2022; Proulx & Morey, 2021; Rubin, 2023b; van Rooij & Baggio, 2021). This sort of work often calls for a greater focus on theory and theory development (e.g., Dames et al., 2024; Flis, 2022; Lavelle, 2023; Szollosi & Donkin, 2021).

There’s also work questioning the rationale for and implementation of various open science reforms, such as preregistration and open data (e.g., Berberi & Roche, 2022; Hicks, 2023; Navarro, 2020; Prosser et al., 2023; Rubin, 2020). One concern here is that these research practices may not translate well across diverse scientific disciplines and paradigms (e.g., Khan et al., 2024; Lamb et al., 2024; Lash & Vandenbroucke, 2012; MacEachern et al., 2019; Pownall, 2024).

Finally, there’s been a continuous stream of articles arguing that metascience has a biased view of science that tends to exclude minority group scientists and approaches (e.g., Bazzoli, 2022; Hamlin, 2017; Hostler, 2024; Leonelli, 2022; Whitaker & Guest, 2020; Ulpts, 2024). There’s also a really interesting line of work that examines the sociology of the metascience movement, dealing with its roots in psychology and its scandalizing and moralizing tendencies (Flis, 2019; Penders, 2024; Peterson & Panofsky, 2021, 2023).

There are further examples of these and other lines of work in the “Articles by Topic” section of this list of 200+ critical metascience articles. Note that these articles are authored by scholars from a variety of disciplines, including statisticians, natural scientists, psychologists, political scientists, sociologists, ethnographers, science and technology studies scholars, philosophers of science, and, of course, metascientists! I’m sure that many of these scholars don’t identify as “critical metascientists,” and some may even actively reject this label, which is fine! What unites the contributions in this list is not a shared identity but a shared focus on questioning metascience’s commonly-accepted assumptions, approaches, problems, and solutions. Hence, just as you don’t have to be a “metascientist” to do metascience (James Wilsdon, quoted in Stafford, 2025), you don’t have to be a “critical metascientist” to do critical metascience!

What’s the Relationship Between Metascience and Critical Metascience?

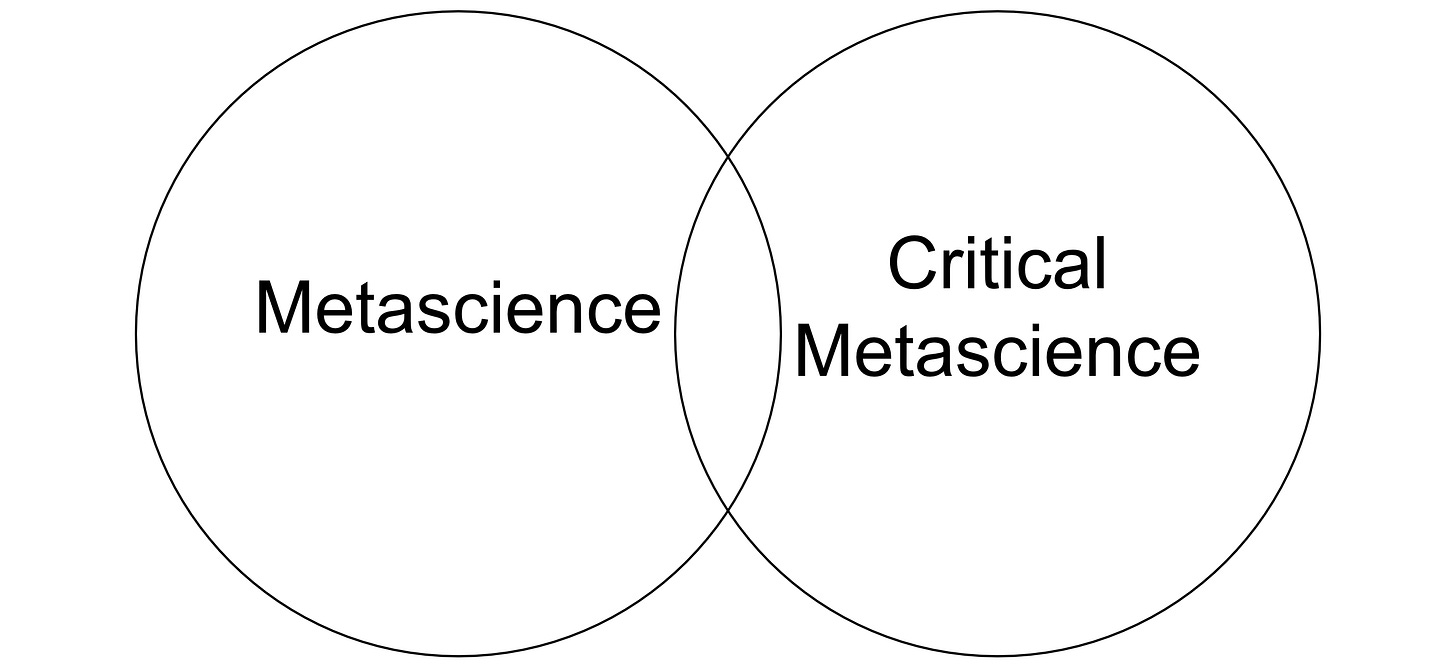

It’s interesting to consider the relationships that might exist between metascience and critical metascience. Here, I consider four possibilities.

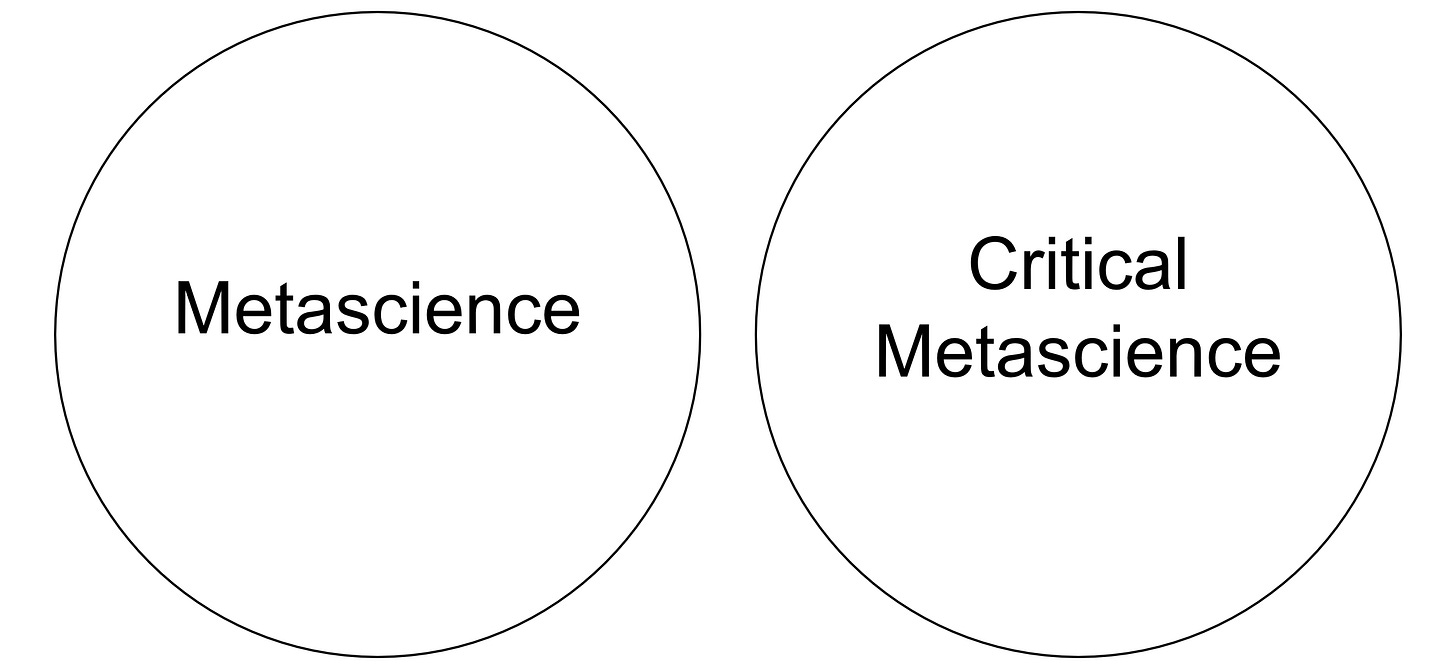

First, the two areas could be considered as being completely separate from one another.

One advantage of this model is that the clear separation between the two areas is likely to facilitate paradigmatic criticism. As Miller (2025) explained, “only an outsider, who adheres to a different conceptual framework, and isn’t committed to the insider’s standards, can thoroughly criticize the insider’s framework” (p. 44; see also Longino, 1990, p. 80). However, this model may also result in quite strong “us” and “them” relations that cause group polarization and intergroup bias. This model also fails to acknowledge that metascientists may sometimes engage in paradigmatic criticism (Syed, 2025). So, instead, we might consider a model in which there’s some overlap between the two areas.

In this second model, metascientists may sometimes step back to criticize some of their field’s core assumptions, and critical metascientists may accept some of these core assumptions while criticizing others. This model continues to facilitate paradigmatic criticism, but it’s less exclusionary and separationist than the first model and, hopefully, more likely to lead to productive interactions. Hence, it’s my preferred model.

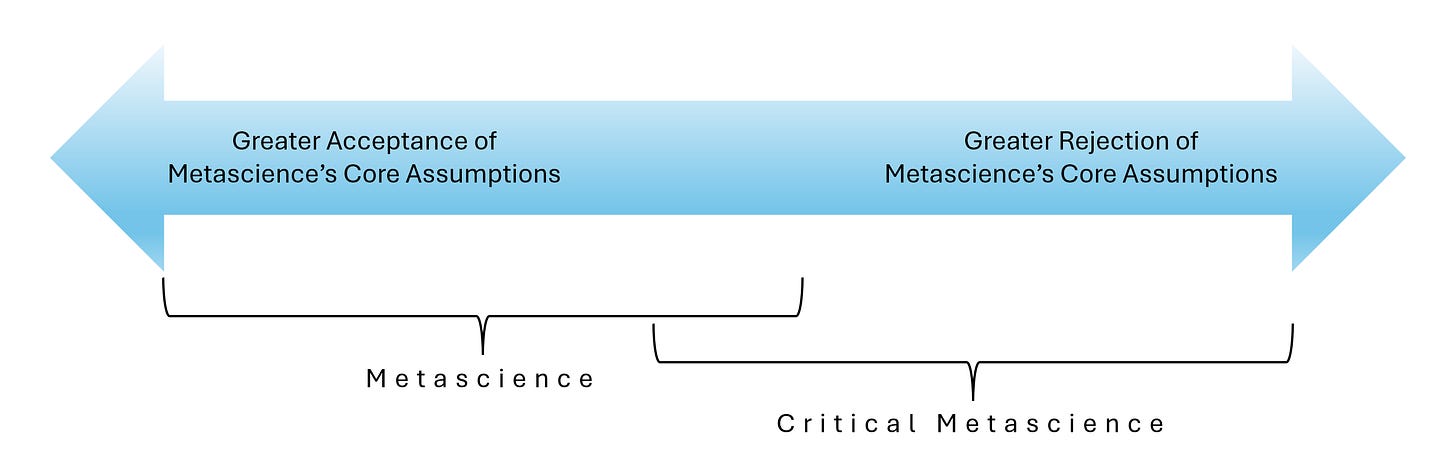

Another way to conceive this second model is as a continuum ranging from greater acceptance of metascience’s core assumptions at one end to greater rejection of those assumptions at the other end.

In this case, more conventional criticism would occur towards the left end of the continuum, and more disruptive, paradigmatic criticism would occur towards the right end of the continuum. Again, this model is more flexible than the first because it allows the same people to occupy different points along the continuum at different times and for different projects.3

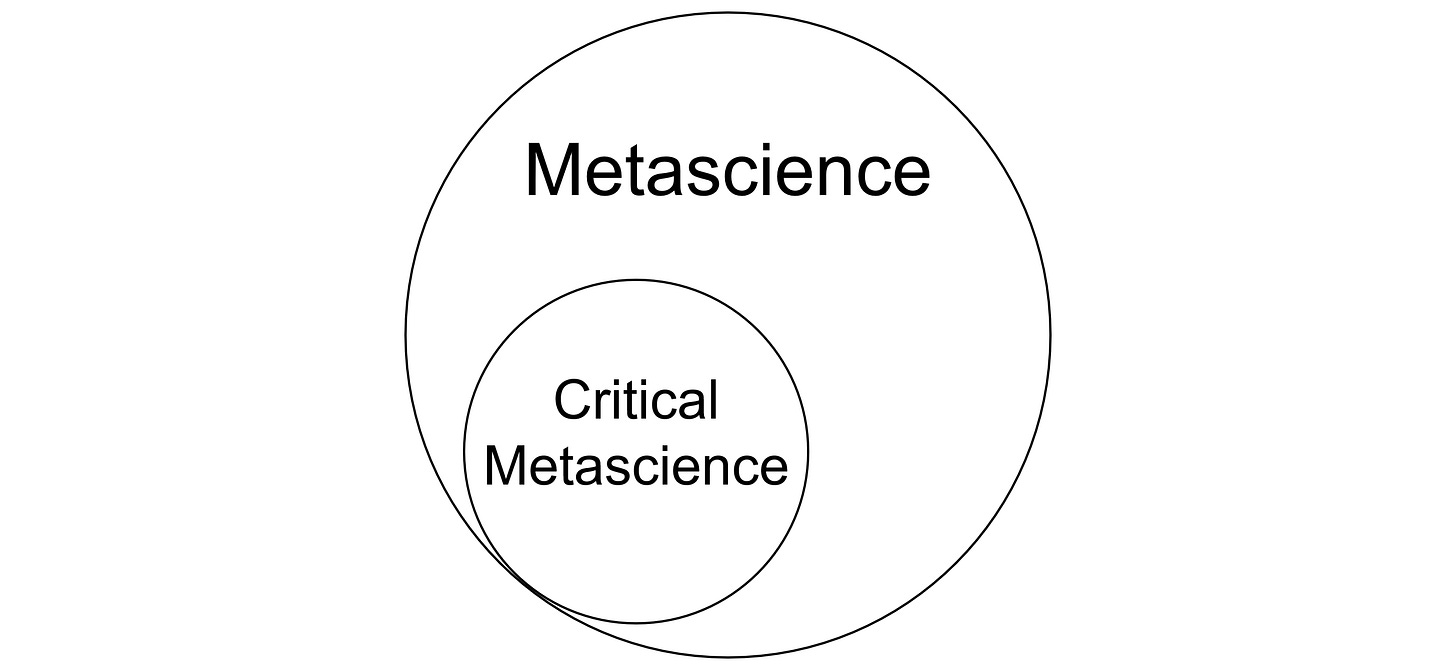

We can quickly consider two further models. First, we could view critical metascience as a subfield of metascience.

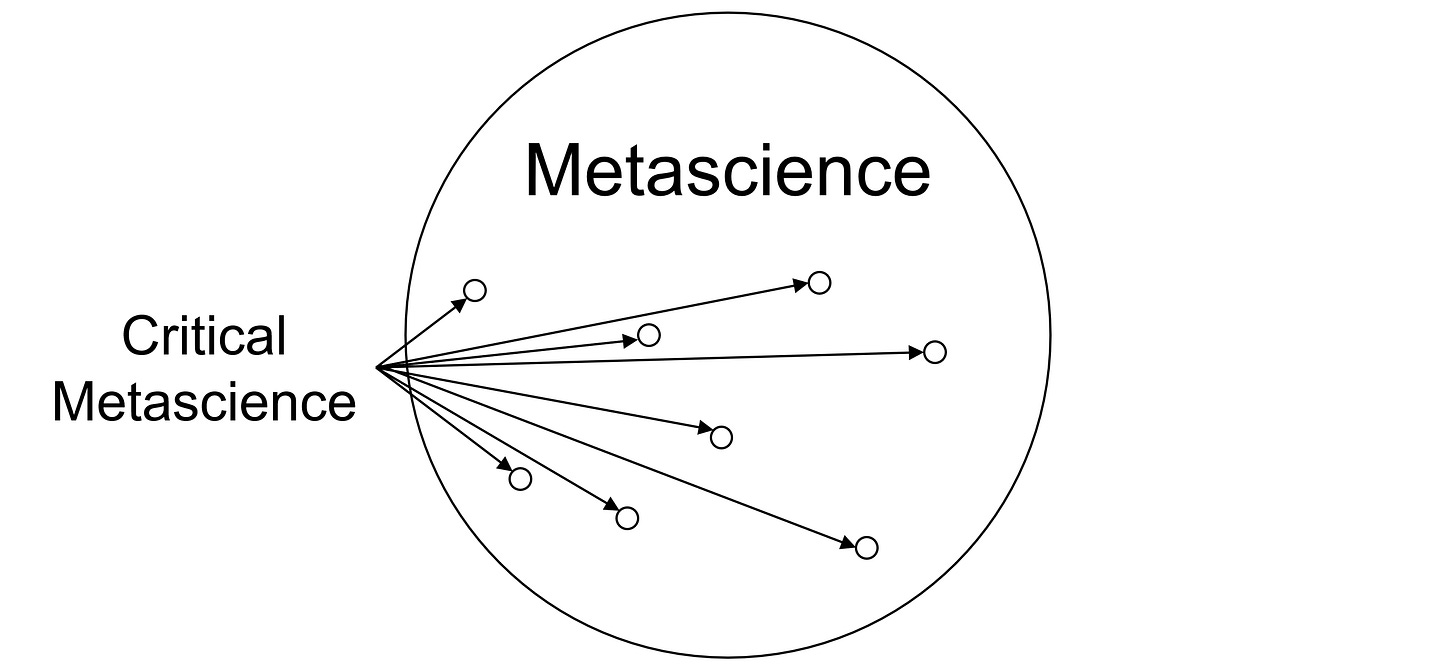

Second, we could go further and consider critical metascience as being peppered into all aspects of metascience.

The problem with these last two models is that the criticism comes from within metascience. Hence, it’s more likely to be grounded in metascience’s background assumptions and less likely to challenge those assumptions. Consequently, these last two models are less likely to generate the more radical, paradigmatic criticism that characterizes critical metascience. Indeed, it would be self-contradictory and epistemically incoherent for the majority of metascientists to routinely reject their own field’s central assumptions, as implied in the last model.

What Needs to Change and Why?

To end, let me try to address the questions we posed in our symposium: “What needs to change and why?” I think one important change is for there to be greater recognition and dialogue between metascience and critical metascience.

For its part, metascience champions scientific criticism. For example, it advocates adversarial collaborations, red teams, effective peer review, error detection, and self-correction, and it encourage scientists to “bend over backwards to show how [they]’re maybe wrong” (Feynman, 1974). Consequently, it should welcome critical metascience as a useful addition to its own self-criticism toolkit. Of course, metascientists don’t always need to concede to critical metascience arguments, but they should at least engage with those arguments publicly, formally, and carefully (Longino, 1990, p. 78; O’Rourke-Friel, 2025; Rubin, 2023b).

And, it takes two to tango! So, critical metascientists need to be prepared to reach out to metascientists in order to have productive exchanges rather than to simply criticize from afar (for a good example, see Pham & Oh’s [2021a, 2021b] discussion with Simmons et al. [2021a, 2021b] about preregistration). They should also be careful not to artificially homogenize metascience or criticize straw-person or outdated versions of metascience arguments (Field, 2022; Rubin, 2023b; Syed, 2025). Finally, they should be reflexive, continuously questioning their own perspectives, biases, and positionality (Bashiri et al., 2025, p. 7).

And why do we need this change? Well, I think that critical metascience can help to improve metascience by making it more objective. As Popper (1976) explained:

Scientific objectivity is based solely upon a critical tradition which, despite resistance, often makes it possible to criticize a dominant dogma. To put it another way, the objectivity of science is…[the result] of the friendly-hostile division of labour among scientists (p. 95)

Critical metascience can play an important part in Popper’s “friendly-hostile division of labour” by offering a special type of criticism that exposes and challenges potential biases and dogma in metascience and by improving its objectivity and approach.

Q&A

The symposium ended with a really interesting Q&A session. One issue that came up was a concern that critical metascience arguments can be misappropriated by bad actors who want to sabotage science reform in order to further their anti-science agenda. I agree that this is a danger. However, this point should not be used as a justification for ignoring critical views. If we go down that road, then, to be consistent, we must also ignore activist metascientists’ criticisms of the status quo because their narrative about the replication crisis and the need for urgent widespread reform can also be co-opted by bad actors for anti-science reasons (Biagioli & Pottage, 2022; Jamieson, 2018; Levy & Johns, 2016; O’Grady, 2025; Nosek, 2025). In summary, both critical and activist metascience arguments run the risk of misappropriation, but that doesn’t imply that those arguments should be suppressed or ignored. It just means that we need to be careful about how we communicate our arguments in order to reduce the potential for their misuse.

More generally, as I mentioned earlier, critical metascience arguments are not necessarily anti-reform arguments. They may also be arguments for alternative reforms and/or alternative implementations of current reforms.

Finally, not every part of the scientific status quo may be problematic and in need of reform! Critical metascience can help to ensure we don't throw out the baby with the bathwater!

Citation

Rubin, M. (2025). What is critical metascience and why is it important? PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/4tpk8_v2

References

Adda, J., Decker, C., & Ottaviani, M. (2020). p-hacking in clinical trials and how incentives shape the distribution of results across phases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(24), 13386-13392. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1919906117

Agnoli, F., Wicherts, J. M., Veldkamp, C. L., Albiero, P., & Cubelli, R. (2017). Questionable research practices among Italian research psychologists. PloS one, 12(3), e0172792. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172792

Antonetti, P., Valor, C. & Božič, B. (2025). Mitigating moral emotions after crises: A reconceptualization of organizational responses. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-025-06042-5

Baker, M. (2016). 1,500 scientists lift the lid on reproducibility. Nature 533, 452–454 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/533452a

Banks, G. C., Rogelberg, S. G., Woznyj, H. M., Landis, R. S., & Rupp, D. E. (2016). Evidence on questionable research practices: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Journal of Business and Psychology, 31, 323-338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-016-9456-7

Bashiri, F., Perez Vico, E., & Hylmö, A. (2025). Scholar-activism as an object of study in a diverse literature: preconditions, forms, and implications. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 12(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05573-6

Bastian, H. (2021, October 31). The metascience movement needs to be more self-critical. PLOS Blogs: Absolutely Maybe. https://absolutelymaybe.plos.org/2021/10/31/the-metascience-movement-needs-to-be-more-self-critical/

Bazzoli, A. (2022). Open science and epistemic pluralism: A tale of many perils and some opportunities. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 15(4), 525-528. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2022.67

Berberi, I., & Roche, D. G. (2022). No evidence that mandatory open data policies increase error correction. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 6(11), 1630-1633. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01879-9

Biagioli, M., & Pottage, A. (2022). Dark transparency: Hyper-ethics at Trump’s EPA. Los Angeles Review of Books, 38. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/dark-transparency-hyper-ethics-at-trumps-epa/

Bishop, D. V. (2019). Rein in the four horsemen of irreproducibility. Nature, 568(7753), 435-436. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-01307-2

Bohman, J. (2021). Critical theory. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2021/entries/critical-theory/

Bosco, F. A., Aguinis, H., Field, J. G., Pierce, C. A., & Dalton, D. R. (2016). HARKing's threat to organizational research: Evidence from primary and meta‐analytic sources. Personnel psychology, 69(3), 709-750. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12111

Brodeur, A., Carrell, S., Figlio, D., & Lusher, L. (2023). Unpacking p-hacking and publication bias. American Economic Review, 113(11), 2974-3002. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20210795

Chambers, C. D., Feredoes, E., Muthukumaraswamy, S. D., & Etchells, P. (2014). Instead of “playing the game” it is time to change the rules: Registered Reports at AIMS Neuroscience and beyond. AIMS Neuroscience, 1(1), 4-17. http://doi.org/10.3934/Neuroscience.2014.1.4

Chambers, C. D., & Tzavella, L. (2022). The past, present and future of Registered Reports. Nature Human Behaviour, 6, 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01193-7

Dalton, D. R., Aguinis, H., Dalton, C. M., Bosco, F. A., & Pierce, C. A. (2012). Revisiting the file drawer problem in meta‐analysis: An assessment of published and nonpublished correlation matrices. Personnel Psychology, 65(2), 221-249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2012.01243.x

Dames, H., Musfeld, P., Popov, V., Oberauer, K., & Frischkorn, G. T. (2024). Responsible research assessment should prioritize theory development and testing over ticking open science boxes. Meta-Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.15626/MP.2023.3735

De Boeck, P., & Jeon, M. (2018). Perceived crisis and reforms: Issues, explanations, and remedies. Psychological Bulletin, 144(7), 757–777. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000154

Devezer, B., Nardin, L. G., Baumgaertner, B., & Buzbas, E. O. (2019). Scientific discovery in a model-centric framework: Reproducibility, innovation, and epistemic diversity. PloS one, 14(5), Article e0216125. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216125

Devezer, B., Navarro, D. J., Vandekerckhove, J., & Ozge Buzbas, E. (2021). The case for formal methodology in scientific reform. Royal Society Open Science, 8(3), Article 200805. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.200805

Erasmus, A. (2024). p-hacking: Its costs and when it is warranted. Erkenntnis, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-024-00834-3

Errington, T. M., Denis, A., Perfito, N., Iorns, E., & Nosek, B. A. (2021). Reproducibility in cancer biology: Challenges for assessing replicability in preclinical cancer biology. Elife, 10, Article e67995. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.67995

Fanelli, D. (2018). Opinion: Is science really facing a reproducibility crisis, and do we need it to? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(11), 2628-2631. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1708272114

Feest, U. (2019). Why replication is overrated. Philosophy of Science, 86(5), 895-905. https://doi.org/10.1086/705451

Feest, U., & Devezer, B. (2025). Toward a more accurate notion of exploratory research (and why it matters). PhilSci Archive. https://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/24482/

Feynman, R. P. (1974). Cargo cult science: Some remarks on science, pseudoscience, and learning how to not fool yourself. Caltech’s 1974 commencement address. https://calteches.library.caltech.edu/51/2/CargoCult.htm

Fiedler, K., & Schwarz, N. (2016). Questionable research practices revisited. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(1), 45-52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615612150

Field, S. M. (2022). Charting the constellation of science reform. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/udfw4

Field, S. M., & Pownall, M. (2025). Subjectivity is a feature, not a flaw: A call to unsilence the human element in science. OSF Preprints. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/ga5fb_v1

Firestein, S. (2012). Ignorance: How it drives science. Oxford University Press.

Firestein, S. (2016, February 14). Why failure to replicate findings can actually be good for science. LA Times. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-0214-firestein-science-replication-failure-20160214-story.html

Flis, I. (2019). Psychologists psychologizing scientific psychology: An epistemological reading of the replication crisis. Theory & Psychology, 29(2), 158-181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354319835322

Flis, I. (2022). The function of literature in psychological science. Review of General Psychology, 26(2), 146-156. https://doi.org/10.1177/10892680211066466

Fraser, H., Parker, T., Nakagawa, S., Barnett, A., & Fidler, F. (2018). Questionable research practices in ecology and evolution. PloS One, 13(7), e0200303. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200303

Gervais, W. M. (2021). Practical methodological reform needs good theory. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(4), 827-843. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620977471

Grant, S., Corker, K. S., Mellor, D. T., Stewart, S. L. K., Cashin, A. G., Lagisz, M., … Nosek, B. A. (2025, February 3). TOP 2025: An update to the transparency and openness promotion guidelines. MetaArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31222/osf.io/nmfs6_v2

Greenfield, P. M. (2017). Cultural change over time: Why replicability should not be the gold standard in psychological science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(5), 762-771. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617707314

Greenwald, A. G., Pratkanis, A. R., Leippe, M. R., & Baumgardner, M. H. (1986). Under what conditions does theory obstruct research progress? Psychological Review, 93(2), 216–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.93.2.216

Gupta, A., & Bosco, F. (2023). Tempest in a teacup: An analysis of p-hacking in organizational research. PLOS One, 18(2), e0281938. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281938

Guttinger, S. (2020). The limits of replicability. European Journal for Philosophy of Science, 10(2), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13194-019-0269-1

Haig, B. D. (2022). Understanding replication in a way that is true to science. Review of General Psychology, 26(2), 224-240. https://doi.org/10.1177/10892680211046514

Hamlin, J. K. (2017). Is psychology moving in the right direction? An analysis of the evidentiary value movement. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(4), 690-693. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616689062

Hardwicke, T. E., & Wagenmakers, E. (2023). Reducing bias, increasing transparency, and calibrating confidence with preregistration. Nature Human Behaviour, 7, 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01497-2

Hartgerink, C. H. J. (2017). Reanalyzing Head et al. (2015): Investigating the robustness of widespread p-hacking. PeerJ, 5:e3068. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3068

Hartgerink, C. H. J., & Wicherts, J. M. (2016). Research practices and assessment of research misconduct. ScienceOpen Research. https://doi.org/10.14293/S2199-1006.1.SOR-SOCSCI.ARYSBI.v1

Hauswald, R. (2021). The epistemic effects of close entanglements between research fields and activist movements. Synthese, 198, 597–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-02047-y

Hicks, D. J. (2023). Open science, the replication crisis, and environmental public health. Accountability in Research, 30(1), 34-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2021.1962713

Horbach, S. P. J. M., Aagaard, K., & Schneider, J. W. (2024). Meta-research: How problematic citing practices distort science. MetaArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31222/osf.io/aqyhg

Hostler, T. J. (2024). Research assessment using a narrow definition of “research quality” is an act of gatekeeping: A comment on Gärtner et al. (2022). Meta-Psychology, 8. https://doi.org/10.15626/MP.2023.3764

Hull, D. L. (1988). Science as a process: An evolutionary account of the social and conceptual development of science. University of Chicago Press.

Iliadis, A., & Russo, F. (2016). Critical data studies: An introduction. Big Data & Society, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951716674238

Iso-Ahola, S. E. (2020). Replication and the establishment of scientific truth. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 2183. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02183

Jamieson, K. H. (2018). Crisis or self-correction: Rethinking media narratives about the well-being of science. PNAS,115(11), 2620-2627. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1708276114

Kerr, N. L. (1998). HARKing: Hypothesizing after the results are known. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2, 196-217. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0203_4

Kessler, A., Likely, R., & Rosenberg, J. M. (2021). Open for whom? The need to define open science for science education. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 58(10), 1590-1595. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21730

Khan, S., Hirsch, J. S., & Zubida, O. Z. (2024). A dataset without a code book: Ethnography and open science. Frontiers in Sociology, 9, Article 1308029. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2024.1308029

Kim, U., Park, Y. S., & Park, D. (2000). The challenge of cross-cultural psychology: The role of the indigenous psychologies. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31(1), 63-75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022100031001006

Knibbe, M., de Rijcke, S., & Penders, B. (2025). Care for the soul of science: Equity and virtue in reform and reformation. Cultures of Science, 8(1), 12-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/20966083251329632

Lakatos, I. (1978). The methodology of scientific research programmes (Philosophical Papers, Volume I). Cambridge University Press.

Lamb, D., Russell, A., Morant, N., & Stevenson, F. (2024). The challenges of open data sharing for qualitative researchers. Journal of Health Psychology, 29(7), 659-664. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591053241237620

Lash, T. L., & Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2012). Commentary: Should preregistration of epidemiologic study protocols become compulsory? Reflections and a counterproposal. Epidemiology, 23(2), 184-188. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e318245c05b

Lavelle, J. S. (2023, October 2). Growth from uncertainty: Understanding the replication 'crisis' in infant psychology. PhilSci Archive. https://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/22679/

Leonelli, S. (2018). Rethinking reproducibility as a criterion for research quality. Including a symposium on Mary Morgan: Curiosity, imagination, and surprise. Research in the History of Economic Thought and Methodology, 36B (pp. 129-146). Emerald Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0743-41542018000036B009

Leonelli, S. (2022). Open science and epistemic diversity: Friends or foes? Philosophy of Science, 89(5), 991-1001. https://doi.org/10.1017/psa.2022.45

Leung, K. (2011). Presenting post hoc hypotheses as a priori: Ethical and theoretical issues. Management and Organization Review, 7(3), 471–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2011.00222.x

Levy, K. E., & Johns, D. M. (2016). When open data is a Trojan Horse: The weaponization of transparency in science and governance. Big Data & Society, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951715621568

Lewandowsky, S., & Oberauer, K. (2020). Low replicability can support robust and efficient science. Nature Communications, 11, Article 358. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-14203-0

Lilienfeld, S. O. (2020). Embracing unpopular ideas: Introduction to the special section on heterodox issues in psychology. Archives of Scientific Psychology, 8(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1037/arc0000072

Linden, A. H., Pollet, T. V., & Hönekopp, J. (2024). Publication bias in psychology: A closer look at the correlation between sample size and effect size. PLOS One, 19(2), e0297075. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0297075

Linder, C., & Farahbakhsh, S. (2020). Unfolding the black box of questionable research practices: Where is the line between acceptable and unacceptable practices? Business Ethics Quarterly, 30(3), 335–360. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2019.52

Longino, H. E. (1990). Science as social knowledge: Values and objectivity in scientific inquiry. Princeton University Press.

MacEachern, Steven N., & Van Zandt, T. (2019). Preregistration of modeling exercises may not be useful. Computational Brain & Behavior, 2, 179-182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42113-019-00038-x

Malich, L., & Rehmann-Sutter, C. (2022). Metascience is not enough: A plea for psychological humanities in the wake of the replication crisis. Review of General Psychology, 26(2), 261-273. https://doi.org/10.1177/10892680221083876

Mathur, M. B., & VanderWeele, T. J. (2021). Estimating publication bias in meta‐analyses of peer‐reviewed studies: A meta‐meta‐analysis across disciplines and journal tiers. Research Synthesis Methods, 12(2), 176-191. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1464

Metascience can improve science - but it must be useful to society, too. (2025). Nature, 643, p. 304. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-02065-0

Miller, B. (2025). The social dimensions of scientific knowledge: Consensus, controversy, and coproduction. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108588782

Miller, J. D., Phillips, N. L., & Lynam, D. R. (2025). Questionable research practices violate the American Psychological Association’s Code of Ethics. Journal of Psychopathology and Clinical Science, 134(2), 113–114. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000974

Mohseni, A. (2020). HARKing: From misdiagnosis to misprescription. PhilSci Archive. https://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/18523/

Moody, J. W., Keister, L. A., & Ramos, M. C. (2022). Reproducibility in the social sciences. Annual Review of Sociology, 48, 65-85. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-090221-035954

Moran, C., Richard, A., Wilson, K., Twomey, R., & Coroiu, A. (2022). I know it’s bad, but I have been pressured into it: Questionable research practices among psychology students in Canada. Canadian Psychology, 64(1), 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000326

Morawski, J. (2020). Psychologists’ psychologies of psychologists in a time of crisis. History of Psychology, 23(2), 176-198. https://doi.org/10.1037/hop0000140

Morawski, J. (2022). How to true psychology’s objects. Review of General Psychology, 26(2), 157-171. https://doi.org/10.1177/10892680211046518

Munafò, M. R., Nosek, B. A., Bishop, D. V., Button, K. S., Chambers, C. D., Percie du Sert, N., ... & Ioannidis, J. P. (2017). A manifesto for reproducible science. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(1), Article 0021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-016-0021

Nagy, T., Hergert, J., Elsherif, M., Wallrich, L., Schmidt, K., Waltzer, T., ... & Rubínová, E. (2025). Bestiary of questionable research practices in psychology. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 8(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/25152459251348431

Navarro, D. (2020, September 23). Paths in strange spaces: A comment on preregistration. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/wxn58

Nielsen, M., & Qiu, K. (2018). A vision of metascience: An engine of improvement for the social processes of science. Science++ Project. https://scienceplusplus.org/metascience/#learning-from-the-renaissance-in-social-psychology

Nelson, L. D., Simmons, J., & Simonsohn, U. (2018). Psychology’s renaissance. Annual Review of Psychology, 69, 511-534. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011836

Nosek, B. A. (2025). Science becomes trustworthy by constantly questioning itself. PLoS Biol 23(8), Article e3003334. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3003334

Nosek, B. A., Spies, J. R., & Motyl, M. (2012). Scientific utopia: II. Restructuring incentives and practices to promote truth over publishability. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(6), 615-631. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612459058

Nosek, B. A. (2019, June 11th). Strategy for culture change. Centre for Open Science. https://www.cos.io/blog/strategy-for-culture-change

Nosek, B. A., & Lakens, D. (2014). Registered reports. Social Psychology, 45(3), 137-141. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000192

Oberauer, K., & Lewandowsky, S. (2019). Addressing the theory crisis in psychology. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 26, 1596–1618. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-019-01645-2

O’Boyle, E. H., Banks, G. C., & Gonzalez-Mulé, E. (2014). The chrysalis effect: How ugly initial results metamorphosize into beautiful articles. Journal of Management, 43(2), 376-399. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527133

O’Boyle, E. H., & Götz, M. (2022). Questionable research practices. In L. J. Jussim, J. A. Krosnick, & S. T. Stevens (Eds), Research integrity: Best practices for the social and behavioral sciences (pp. 260-294). Oxford University Press.

O’Grady, C. (2025, June 10). Science’s reform movement should have seen Trump’s call for ‘gold standard science’ coming, critics say. Science Adviser. https://www.science.org/content/article/science-s-reform-movement-should-have-seen-trump-s-call-gold-standard-science-coming

Open Science Collaboration. (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349(6251), Article aac4716. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4716

O’Rourke-Friel (2025). Social epistemology for individuals like us. Episteme. https://doi.org/10.1017/epi.2024.59

Parker, I. (2007). Critical psychology: What it is and what it is not. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00008.x

Pashler, H., & Harris, C. R. (2012). Is the replicability crisis overblown? Three arguments examined. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(6), 531-536. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612463401

Pashler, H., & Wagenmakers, E. J. (2012). Editors’ introduction to the special section on replicability in psychological science: A crisis of confidence? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(6), 528-530. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612465253

Paulus, D., de Vries, G., Janssen, M., & Van de Walle, B. (2022). The influence of cognitive bias on crisis decision-making: Experimental evidence on the comparison of bias effects between crisis decision-maker groups. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 82, Article 103379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103379

Penders, B. (2024). Scandal in scientific reform: The breaking and remaking of science. Journal of Responsible Innovation, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2024.2371172

Peterson, D., & Panofsky, A. (2021). Arguments against efficiency in science. Social Science Information, 60(3), 350-355. https://doi.org/10.1177/05390184211021383

Peterson, D., & Panofsky, A. (2023). Metascience as a scientific social movement. Minerva. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-023-09490-3

Pethick, S., Wass, M. N., & Michaelis, M. (2025). Is there a reproducibility crisis? On the need for evidence-based approaches. International Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02698595.2025.2538937

Pham, M. T., & Oh, T. T. (2021a). On not confusing the tree of trustworthy statistics with the greater forest of good science: A comment on Simmons et al.’s perspective on pre‐registration. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 31(1), 181-185. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcpy.1213

Pham, M. T., & Oh, T. T. (2021b). Preregistration is neither sufficient nor necessary for good science. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 31(1), 163-176. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcpy.1209

Pickett, J. T., & Roche, S. P. (2018). Questionable, objectionable or criminal? Public opinion on data fraud and selective reporting in science. Science and Engineering Ethics, 24, 151-171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9886-2

Popper, K. R. (1976). The logic of the social sciences. In T. W. Adorno, H. Albert, R. Dhrendorf, J. Habermas, H. Pilot, & K. R. Popper, The positivist dispute in German sociology (pp. 87-104). Heineman.

Popper, K. R. (1994). Knowledge and the body-mind problem: In defence of interaction. Routledge.

Pownall, M. (2024). Is replication possible for qualitative research? A response to Makel et al. (2022). Educational Research and Evaluation, 29(1–2), 104–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2024.2314526

Prosser, A. M. B., Hamshaw, R., Meyer, J., Bagnall, R., Blackwood, L., Huysamen, M., ... & Walter, Z. (2023). When open data closes the door: Problematising a one size fits all approach to open data in journal submission guidelines. British Journal of Social Psychology, 62(4), 1635-1653. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12576

Proulx, T., & Morey, R. D. (2021). Beyond statistical ritual: Theory in psychological science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(4), 671-681. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916211017098

Quintana, D. S., Heathers, J. A. J. (Hosts) (2023, April 26). 168: Meta-meta-science, Everything Hertz [Audio podcast]. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/CSJ3X

Ramos, M. L. F. (2025). Balanced examination of positive publication bias impact. Accountability in Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2025.2538066

Ravn, T., & Sørensen, M. P. (2021). Exploring the gray area: Similarities and differences in questionable research practices (QRPs) across main areas of research. Science and Engineering Ethics, 27(4), 40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-021-00310-z

Reis, D., & Friese, M. (2022). The myriad forms of p-hacking. In W. O'Donohue, A. Masuda, & S. Lilienfeld (Eds), Avoiding questionable research practices in applied psychology. Spinger. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04968-2_5

Robinson-Greene, R. (2017). The moral dimensions of the research reproducibility crisis. The Prindle Post. https://www.prindlepost.org/2017/10/moral-dimensions-research-reproducibility-crisis/

Rooprai, P., Islam, N., Salameh, J. P., Ebrahimzadeh, S., Kazi, A., Frank, R., Ramsay, T., Mathur, M. B., Absi, M., Khalil, A., Kazi, S., Dawit, H., Lam, E., Fabiano, N., & McInnes, M. D. (2023). Is there evidence of p-hacking in imaging research? Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal, 74(3), 497-507. https://doi.org/10.1177/08465371221139418

Rubin, M. (2017a). Do p values lose their meaning in exploratory analyses? It depends how you define the familywise error rate. Review of General Psychology, 21(3), 269-275. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000123

Rubin, M. (2017b). When does HARKing hurt? Identifying when different types of undisclosed post hoc hypothesizing harm scientific progress. Review of General Psychology, 21(4), 308-320. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000128

Rubin, M. (2020). Does preregistration improve the credibility of research findings? The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 16(4), 376–390. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.16.4.p376

Rubin, M. (2022). The costs of HARKing. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 73(2), 535-560. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjps/axz050

Rubin, M. (2023a, May 4). Opening up open science to epistemic pluralism: Comment on Bazzoli (2022) and some additional thoughts. Critical Metascience. https://doi.org/10.31222/osf.io/dgzxa

Rubin, M. (2023b). Questionable metascience practices. Journal of Trial and Error, 4(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.36850/mr4

Rubin, M. (2024). Type I error rates are not usually inflated. Journal of Trial and Error, 4(2), 46-71. https://doi.org/10.36850/4d35-44bd

Rubin, M. (2025a). A brief review of research that questions the impact of questionable research practices. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ah9wb_v3

Rubin, M. (2025b). The replication crisis is less of a “crisis” in Lakatos’ philosophy of science than it is in Popper’s. European Journal for Philosophy of Science, 15(5). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13194-024-00629-x

Rubin, M., & Donkin, C. (2024). Exploratory hypothesis tests can be more compelling than confirmatory hypothesis tests. Philosophical Psychology, 37(8), 2019-2047. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2022.2113771

Russell, B. (1912). On the notion of cause. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 13, 1–26. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4543833

Sacco, D. F., Brown, M., & Bruton, S. V. (2019). Grounds for ambiguity: Justifiable bases for engaging in questionable research practices. Science and Engineering Ethics, 25(5), 1321-1337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-018-0065-x

Schimmack, U. (2020). A meta-psychological perspective on the decade of replication failures in social psychology. Canadian Psychology, 61(4), 364–376. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000246

Schooler, J. (2014). Metascience could rescue the ‘replication crisis’. Nature 515, 9. https://doi.org/10.1038/515009a

Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D., & Simonsohn, U. (2011). False-positive psychology: Undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychological Science, 22(11), 1359-1366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611417632

Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D., & Simonsohn, U. (2021a). Pre‐registration is a game changer. But, like random assignment, it is neither necessary nor sufficient for credible science. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 31(1), 177-180. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcpy.1207

Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D., & Simonsohn, U. (2021b). Pre‐registration: Why and how. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 31(1), 151-162. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcpy.1208

Stafford, T. (2025, July 4). ECR metascientist happy hour. UK Reproducibility Network. https://www.ukrn.org/2025/07/04/ecr-metascientist-happy-hour/

Stanley, T. D., Carter, E. C., & Doucouliagos, H. (2018). What meta-analyses reveal about the replicability of psychological research. Psychological Bulletin, 144(12), 1325-1346. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000169

Stefan, A. M., & Schönbrodt, F. D. (2023). Big little lies: A compendium and simulation of p-hacking strategies. Royal Society Open Science, 10(2), 220346. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.220346

Steltenpohl, C. N., Lustick, H., Meyer, M. S., Lee, L. E., Stegenga, S. M., Reyes, L. S., & Renbarger, R. L. (2023). Rethinking transparency and rigor from a qualitative open science perspective. Journal of Trial & Error, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.36850/mr7

Stroebe, W., & Strack, F. (2014). The alleged crisis and the illusion of exact replication. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(1), 59-71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691613514450

Syed, M. (2025). A tale of two science reform movements. Get Syeducated. https://getsyeducated.substack.com/p/a-tale-of-two-science-reform-movements

Szollosi, A., & Donkin, C. (2021). Arrested theory development: The misguided distinction between exploratory and confirmatory research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(4), 717-724. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620966796

Turner, M. E., & Pratkanis, A. R. (1998). A social identity maintenance model of groupthink. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 73(2-3), 210-235. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1998.2757

UK Metascience Unit. (2025). A year in metascience: The past, present and future of UK metascience (Annex). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/685bcd40c07c71e5a87097d1/the-past-present-future-of-uk-metascience.pdf

Ulpts, S. (2024). Responsible assessment of what research? Beware of epistemic diversity! Meta-Psychology. https://doi.org/10.15626/MP.2023.3797

Ulrich, R., & Miller, J. (2020). Questionable research practices may have little effect on replicability. Elife, 9, e58237. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.58237

Van Aert, R. C., Wicherts, J. M., & Van Assen, M. A. (2019). Publication bias examined in meta-analyses from psychology and medicine: A meta-meta-analysis. PLOS One, 14(4), e0215052. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215052

van Rooij, I., & Baggio, G. (2021). Theory before the test: How to build high-verisimilitude explanatory theories in psychological science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(4), 682-697. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620970604

Vazire, S., & Nosek, B. (2023). Introduction to special topic “Is psychology self-correcting? Reflections on the credibility revolution in social and personality psychology”. Social Psychological Bulletin, 18, 1-4. https://doi.org/10.32872/spb.12927

Vancouver, J. N. (2018). In defense of HARKing. Industrial and Organizational Psychology. 11(1), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2017.89

Wagenmakers, E. J., Wetzels, R., Borsboom, D., van der Maas, H. L., & Kievit, R. A. (2012). An agenda for purely confirmatory research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(6), 632-638. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612463078

Walkup, J. (2021). Replication and reform: Vagaries of a social movement. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, 41(2), 131-133. https://doi.org/10.1037/teo0000171

Wegener, D. T., Pek, J., & Fabrigar, L. R. (2024). Accumulating evidence across studies: Consistent methods protect against false findings produced by p-hacking. PLOS One, 19(8), e0307999. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0307999

Whitaker, K., & Guest, O. (2020). # bropenscience is broken science. The Psychologist, 33, 34-37. https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/volume-33/november-2020/bropenscience-broken-science

Wicherts, J. M., Veldkamp, C. L., Augusteijn, H. E., Bakker, M., Van Aert, R. C., & Van Assen, M. A. (2016). Degrees of freedom in planning, running, analyzing, and reporting psychological studies: A checklist to avoid p-hacking. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, Article 1832. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01832

Wingen, T., Berkessel, J. B., & Englich, B. (2020). No replication, no trust? How low replicability influences trust in psychology. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(4), 454-463. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619877412

Critical psychology and critical data studies both adopt a critical theory approach that examines power structures, ideologies, and social injustices within their respective disciplines (Bohman, 2021). Although some critical metascientists may follow this approach, I view critical metascience as being broader than, and not constrained to, critical theory.

As someone mentioned in the Q&A session at the end of my presentation, this last argument implies an infinite regress of ever more reflective metasciences (e.g., “meta-meta-meta-science”)! However, each new meta-level will criticize a subject that becomes increasingly abstract and obscure. Hence, although I agree that critical metascience should be critiqued, I think we’ll quickly lose interest as we reach even higher levels of abstraction!